Nanotechnology researchers are developing the perfect complement to the power tie: a “power shirt” able to generate electricity to power small electronic devices for soldiers in the field, hikers and others whose physical motion could be harnessed and converted to electrical energy.

The February 14 issue of the journal Nature details how pairs of textile fibers covered with zinc oxide nanowires can generate electrical current using the piezoelectric effect. Combining current flow from many fiber pairs woven into a shirt or jacket could allow the wearer’s body movement to power a range of portable electronic devices. The fibers could also be woven into curtains, tents or other structures to capture energy from wind motion, sound vibration or other mechanical energy.

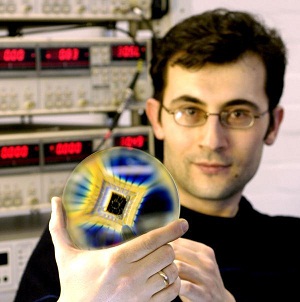

“The fiber-based nanogenerator would be a simple and economical way to harvest energy from physical movement,” said Zhong Lin Wang, a Regents professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “If we can combine many of these fibers in double or triple layers in clothing, we could provide a flexible, foldable and wearable power source that, for example, would allow people to generate their own electrical current while walking.”

The microfiber-nanowire hybrid system builds on the nanowire nanogenerator that Wang’s research team announced in April 2007. That system generates current from arrays of vertically-aligned zinc oxide (ZnO) nanowires that flex beneath an electrode containing conductive platinum tips. The nanowire nanogenerator was designed to harness energy from environmental sources such as ultrasonic waves, mechanical vibrations or blood flow.

The nanogenerators developed by Wang’s research group take advantage of the unique coupled piezoelectric and semiconducting properties of zinc oxide nanostructures, which produce small electrical charges when they are flexed. After a year of development, the original nanogenerators — which are two by three millimeters square — can produce up to 800 nanoamperes and 20 millivolts.

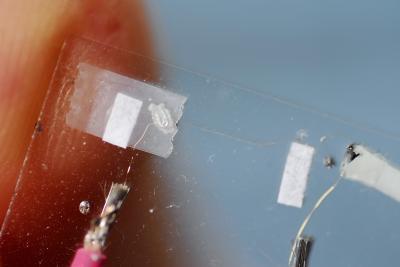

The microfiber generators rely on the same principles, but are made from soft materials and designed to capture energy from low-frequency mechanical energy. They consist of DuPont Kevlar fibers on which zinc oxide nanowires have been grown radially and embedded in a polymer at their roots, creating what appear to be microscopic baby-bottle brushes with billions of bristles. One of the fibers in each pair is also coated with gold to serve as the electrode and to deflect the nanowire tips.

“The two fibers scrub together just like two bottle brushes with their bristles touching, and the piezoelectric-semiconductor process converts the mechanical motion into electrical energy,” Wang explained. “Many of these devices could be put together to produce higher power output.”

Wang and collaborators Xudong Wang and Yong Qin have made more than 200 of the fiber nanogenerators. Each is tested on an apparatus that uses a spring and wheel to move one fiber against the other. The fibers are rubbed together for up to 30 minutes to test their durability and power production.

So far, the researchers have measured current of about four nanoamperes and output voltage of about four millivolts from a nanogenerator that included two fibers that were each one centimeter long. With a much improved design, Wang estimates that a square meter of fabric made from the special fibers could theoretically generate as much as 80 milliwatts of power.

Fabrication of the microfiber nanogenerator begins with coating a 100-nanometer seed layer of zinc oxide onto the Kevlar using magnetron sputtering. The fibers are then immersed in a reactant solution for approximately 12 hours, which causes nanowires to grow from the seed layer at a temperature of 80 degrees Celsius. The growth produces uniform coverage of the fibers, with typical lengths of about 3.5 microns and several hundred nanometers between each fiber.

To help maintain the nanowires’ connection to the Kevlar, the researchers apply two layers of tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) to the fiber. “First we coat the fiber with the polymer, then with a zinc oxide layer,” Wang explained. “Then we grow the nanowires and re-infiltrate the fiber with the polymer. This helps to avoid scrubbing off the nanowires when the fibers rub together.”

Finally, the researchers apply a 300 nanometer layer of gold to some of the nanowire-covered Kevlar. The two different fibers are then paired up and entangled to ensure that a gold-coated fiber contacts a fiber covered only with zinc oxide nanowires. The gold fibers serve as a Shottky barrier with the zinc oxide, substituting for the platinum-tipped electrode used in the original nanogenerator.

To ensure that the current they measured was produced by the piezoelectric-semiconductor effect and not just static electricity, the researchers conducted several tests. They tried rubbing gold fibers together, and zinc oxide fibers together, neither of which produced current. They also reversed the polarity of the connections, which changed the output current and voltage.

By allowing nanowire growth to take place at temperatures as low as 80 degrees Celsius, the new fabrication technique would allow the nanostructures to be grown on virtually any shape or substrate.

As a next step, the researchers want to combine multiple fiber pairs to increase the current and voltage levels. They also plan to improve conductance of their fibers.

However, one significant challenge lies head for the power shirt — washing it. Zinc oxide is sensitive to moisture, so in real shirts or jackets, the nanowires would have to be protected from the effects of the washing machine, Wang noted.

The research was sponsored by the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy and the Emory-Georgia Tech Nanotechnology Center for Personalized and Predictive Oncology.

Story Source:

The above story is reprinted from materials provided by Georgia Institute of Technology, via EurekAlert!, a service of AAAS.

— Nanotechnology researchers are developing the perfect complement to the power tie: a “power shirt” able to generate electricity to power small electronic devices for soldiers in the field, hikers and others whose physical motion could be harnessed and converted to electrical energy.

The February 14 issue of the journal Nature details how pairs of textile fibers covered with zinc oxide nanowires can generate electrical current using the piezoelectric effect. Combining current flow from many fiber pairs woven into a shirt or jacket could allow the wearer’s body movement to power a range of portable electronic devices. The fibers could also be woven into curtains, tents or other structures to capture energy from wind motion, sound vibration or other mechanical energy.

“The fiber-based nanogenerator would be a simple and economical way to harvest energy from physical movement,” said Zhong Lin Wang, a Regents professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “If we can combine many of these fibers in double or triple layers in clothing, we could provide a flexible, foldable and wearable power source that, for example, would allow people to generate their own electrical current while walking.”

The microfiber-nanowire hybrid system builds on the nanowire nanogenerator that Wang’s research team announced in April 2007. That system generates current from arrays of vertically-aligned zinc oxide (ZnO) nanowires that flex beneath an electrode containing conductive platinum tips. The nanowire nanogenerator was designed to harness energy from environmental sources such as ultrasonic waves, mechanical vibrations or blood flow.

The nanogenerators developed by Wang’s research group take advantage of the unique coupled piezoelectric and semiconducting properties of zinc oxide nanostructures, which produce small electrical charges when they are flexed. After a year of development, the original nanogenerators — which are two by three millimeters square — can produce up to 800 nanoamperes and 20 millivolts.

The microfiber generators rely on the same principles, but are made from soft materials and designed to capture energy from low-frequency mechanical energy. They consist of DuPont Kevlar fibers on which zinc oxide nanowires have been grown radially and embedded in a polymer at their roots, creating what appear to be microscopic baby-bottle brushes with billions of bristles. One of the fibers in each pair is also coated with gold to serve as the electrode and to deflect the nanowire tips.

“The two fibers scrub together just like two bottle brushes with their bristles touching, and the piezoelectric-semiconductor process converts the mechanical motion into electrical energy,” Wang explained. “Many of these devices could be put together to produce higher power output.”

Wang and collaborators Xudong Wang and Yong Qin have made more than 200 of the fiber nanogenerators. Each is tested on an apparatus that uses a spring and wheel to move one fiber against the other. The fibers are rubbed together for up to 30 minutes to test their durability and power production.

So far, the researchers have measured current of about four nanoamperes and output voltage of about four millivolts from a nanogenerator that included two fibers that were each one centimeter long. With a much improved design, Wang estimates that a square meter of fabric made from the special fibers could theoretically generate as much as 80 milliwatts of power.

Fabrication of the microfiber nanogenerator begins with coating a 100-nanometer seed layer of zinc oxide onto the Kevlar using magnetron sputtering. The fibers are then immersed in a reactant solution for approximately 12 hours, which causes nanowires to grow from the seed layer at a temperature of 80 degrees Celsius. The growth produces uniform coverage of the fibers, with typical lengths of about 3.5 microns and several hundred nanometers between each fiber.

To help maintain the nanowires’ connection to the Kevlar, the researchers apply two layers of tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) to the fiber. “First we coat the fiber with the polymer, then with a zinc oxide layer,” Wang explained. “Then we grow the nanowires and re-infiltrate the fiber with the polymer. This helps to avoid scrubbing off the nanowires when the fibers rub together.”

Finally, the researchers apply a 300 nanometer layer of gold to some of the nanowire-covered Kevlar. The two different fibers are then paired up and entangled to ensure that a gold-coated fiber contacts a fiber covered only with zinc oxide nanowires. The gold fibers serve as a Shottky barrier with the zinc oxide, substituting for the platinum-tipped electrode used in the original nanogenerator.

To ensure that the current they measured was produced by the piezoelectric-semiconductor effect and not just static electricity, the researchers conducted several tests. They tried rubbing gold fibers together, and zinc oxide fibers together, neither of which produced current. They also reversed the polarity of the connections, which changed the output current and voltage.

By allowing nanowire growth to take place at temperatures as low as 80 degrees Celsius, the new fabrication technique would allow the nanostructures to be grown on virtually any shape or substrate.

As a next step, the researchers want to combine multiple fiber pairs to increase the current and voltage levels. They also plan to improve conductance of their fibers.

However, one significant challenge lies head for the power shirt — washing it. Zinc oxide is sensitive to moisture, so in real shirts or jackets, the nanowires would have to be protected from the effects of the washing machine, Wang noted.

The research was sponsored by the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy and the Emory-Georgia Tech Nanotechnology Center for Personalized and Predictive Oncology.